فإنك تعلم

ولا أعلم

You know of the how

I know of the how-less

Basra,

March 8, 731

March 8, 731

Rabi’a was the daughter of an extremely poor family from Basra, in present Iraq. The family was so poor that her parents decided not to waste too much energy thinking about her name. As she was their fourth child, the couple called her Rabi’a: a word that literally means 'fourth' in Arabic. When her parents died, Rabi’a was sold into slavery.It is believed that one night, her master saw a light surrounding her while she was praying. The image left the man captivated and in the morning he freed her.

From then on, she paved her own way, pushing her body and soul onto the dusty roads of knowledge.

Asceticism is not encouraged in Islam, as its principles and practices run contrary to the religion’s emphasis on being part of the community. Nevertheless, Rabi’a shirked the idea of a regular life. Like many others at the turn of the 9th century, she slowly disappeared towards the desert, carrying but a few belongings, to practice the ‘ilm al-batin, the knowledge of that which lies within.

- “I want to put out the fires of Hell, and burn down the rewards of Paradise, as they block the way to God. I do not want to worship from fear of punishment or for the promise of reward, but simply for the love of God”.

In the desert, Rabi’a led a life of humility and even poverty, showing in this way that having a personal bond to the divine was something that both men and women were capable of striving for.

Indeed, in her lifetime she never called a man her master. Rabi’a thus consciously pursued an independent lifestyle as a woman-poet, wandering through the desert in solitude. In so doing, she was following a path that many female Sufi mystics had charted before her as a means of ensuring personal salvation.

- “I want to put out the fires of Hell, and burn down the rewards of Paradise, as they block the way to God. I do not want to worship from fear of punishment or for the promise of reward, but simply for the love of God”.

In the desert, Rabi’a led a life of humility and even poverty, showing in this way that having a personal bond to the divine was something that both men and women were capable of striving for.

Indeed, in her lifetime she never called a man her master. Rabi’a thus consciously pursued an independent lifestyle as a woman-poet, wandering through the desert in solitude. In so doing, she was following a path that many female Sufi mystics had charted before her as a means of ensuring personal salvation.

-"I should be ashamed to ask for the things of this world from him to whom the world belongs, and how should I ask for them from those to whom it does not belong?"

It is said that Rabi’a’s ascetic practices brought her closer to the Adbal: the society of hidden saints whose great cosmic powers allegedly allowed them to alter their psychic states and withdraw their bodies from physical laws. The legend suggests that she was even able to perform divine miracles because of the intimacy she was able to achieve with God through introspection. When she was asked how she discovered the secret, she responded:

-”You know of the how. I know of the how-less.”

The stories detailing the life and practices of Rabi'a of Basra show a countercultural understanding of the role of gender in society. Indeed, she was the one who first set forth the doctrine of Divine Love known as Ishq-e-Haqeeqi and she is widely considered to be the most important of the early renunciants. Hers was a model of piety that would eventually come to be known as Sufism.

When Rabi’a died at the age of eighty, her only possessions were an old, patched, dress-like mantle, a pottery jug and a reed mat that doubled as her prayer rug. Some say she was buried near Jerusalem, in the Kidron Valley, her tomb becoming a cult destination throughout the Middle Ages.

It is said that Rabi’a’s ascetic practices brought her closer to the Adbal: the society of hidden saints whose great cosmic powers allegedly allowed them to alter their psychic states and withdraw their bodies from physical laws. The legend suggests that she was even able to perform divine miracles because of the intimacy she was able to achieve with God through introspection. When she was asked how she discovered the secret, she responded:

-”You know of the how. I know of the how-less.”

When Rabi’a died at the age of eighty, her only possessions were an old, patched, dress-like mantle, a pottery jug and a reed mat that doubled as her prayer rug. Some say she was buried near Jerusalem, in the Kidron Valley, her tomb becoming a cult destination throughout the Middle Ages.

السياح

Siyaha

Even as specialists in philology, poetry and genealogy were taking great pains to learn from the Bedouins through the practice of rihla, another emerging class of learned men and women in Islam also began to focus on the desert at the turn of the 9th century. They were mystics seeking fundamental alterity in solitude. Like the other learned men, the mystics used rihla to get closer to their master thinkers. Unlike the scholars, however, the mystics soon felt rihla‘s limitations. For them, the rihla tended to lead to only one aspect of knowledge: the dhahir, or knowledge as appearance. The mystics considered themselves to be the bearers of a sort of knowledge that reached beyond obvious causes to decipher the hidden, the batin

. This is how the siyaha, a new form of travel in search of knowledge, emerged.

The term siyaha, or wandering, refers to the lifestyle of the hermit, 'a person who does not know how to take pleasure in the savons of food and drink, who rejects the warmth of the hearth, and who is not fixed in any one place.' The sa’ihun, or vagabond saints, travelled continually in search of I’tibar, or teaching, and istibsar, intuition. By teaching, they learned and practised the exemplary observation of the world while, through istibsar, they cultivated the intuitive faculty of penetrating the essence of beings and things.

Islamic mysticism follows the traditions of early Christianity hermeticism and Hindu asceticism. Both traditions are essential to understanding the rise of Sufism in medieval Islam, and especially the cult of siyaha. Indeed, in addition to the monistic and pantheistic tendencies of a number of Sufi masters, such as al-Hallaj (d. 922), Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240), Ibn Sab‘in (d. 1269) and Ibn al-Faridh (d. 1353), others chose to wander in the desert and in uninhabited places, often for years and in some cases for life, without carrying provisions, in search of enlightenment and inner truth.

Like the scholars who practiced the rihla, the sa’ihun also adopted the Aja’ib as a way to write about their travels and tribulations. These creative travelogues were a mix of personal narrative, description, opinion and anecdote. The Aja’ib brought together the mystic and the scholarly creative literary genres through the principle of autopsia. Although it is not certain that the events they described were real, 'it was even less certain that they were false. They were, above all, difficult to confirm.' The fact that the marvellous operated on the terrain of ambiguity and metamorphosis created a singular connection between the human and the divine, the visible and the invisible, the natural and the supernatural, the ordinary and the extraordinary, and the believable and the unbelievable. Whereas, by adopting the rihla as a travel genre, traditional cosmographers, geographers and historians attempted to give enigma an objective interpretation and the moralists tried to give it a subjective content, in the Aja’ib the mystics and young scholars aimed to experience enigma by imagining nature as a reservoir of symbols, the so called ayats.

The term siyaha, or wandering, refers to the lifestyle of the hermit, 'a person who does not know how to take pleasure in the savons of food and drink, who rejects the warmth of the hearth, and who is not fixed in any one place.' The sa’ihun, or vagabond saints, travelled continually in search of I’tibar, or teaching, and istibsar, intuition. By teaching, they learned and practised the exemplary observation of the world while, through istibsar, they cultivated the intuitive faculty of penetrating the essence of beings and things.

Islamic mysticism follows the traditions of early Christianity hermeticism and Hindu asceticism. Both traditions are essential to understanding the rise of Sufism in medieval Islam, and especially the cult of siyaha. Indeed, in addition to the monistic and pantheistic tendencies of a number of Sufi masters, such as al-Hallaj (d. 922), Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240), Ibn Sab‘in (d. 1269) and Ibn al-Faridh (d. 1353), others chose to wander in the desert and in uninhabited places, often for years and in some cases for life, without carrying provisions, in search of enlightenment and inner truth.

Like the scholars who practiced the rihla, the sa’ihun also adopted the Aja’ib as a way to write about their travels and tribulations. These creative travelogues were a mix of personal narrative, description, opinion and anecdote. The Aja’ib brought together the mystic and the scholarly creative literary genres through the principle of autopsia. Although it is not certain that the events they described were real, 'it was even less certain that they were false. They were, above all, difficult to confirm.' The fact that the marvellous operated on the terrain of ambiguity and metamorphosis created a singular connection between the human and the divine, the visible and the invisible, the natural and the supernatural, the ordinary and the extraordinary, and the believable and the unbelievable. Whereas, by adopting the rihla as a travel genre, traditional cosmographers, geographers and historians attempted to give enigma an objective interpretation and the moralists tried to give it a subjective content, in the Aja’ib the mystics and young scholars aimed to experience enigma by imagining nature as a reservoir of symbols, the so called ayats.

Ayat, or the impossibility

of perception

استحالة الإدراك

︎︎︎The Impossibility of Perception is a personal account created during the last stage of the project Beyond Qafila Thania, a 20-day nomadic residency through the Draa valley, from M’Hamid to Tizint in the Southern Moroccan Desert in November 2017. Beyond Qafila Thania brought together researchers from Sudan, Morocco, Spain, Catalonia, Italy and the Netherlands, working in the fields of architecture, sociology and the visual arts. Together they sought to engage with the cultural, social and geopolitical space of the Sahara desert.

Southern moroccan desert,

November 1, 2017

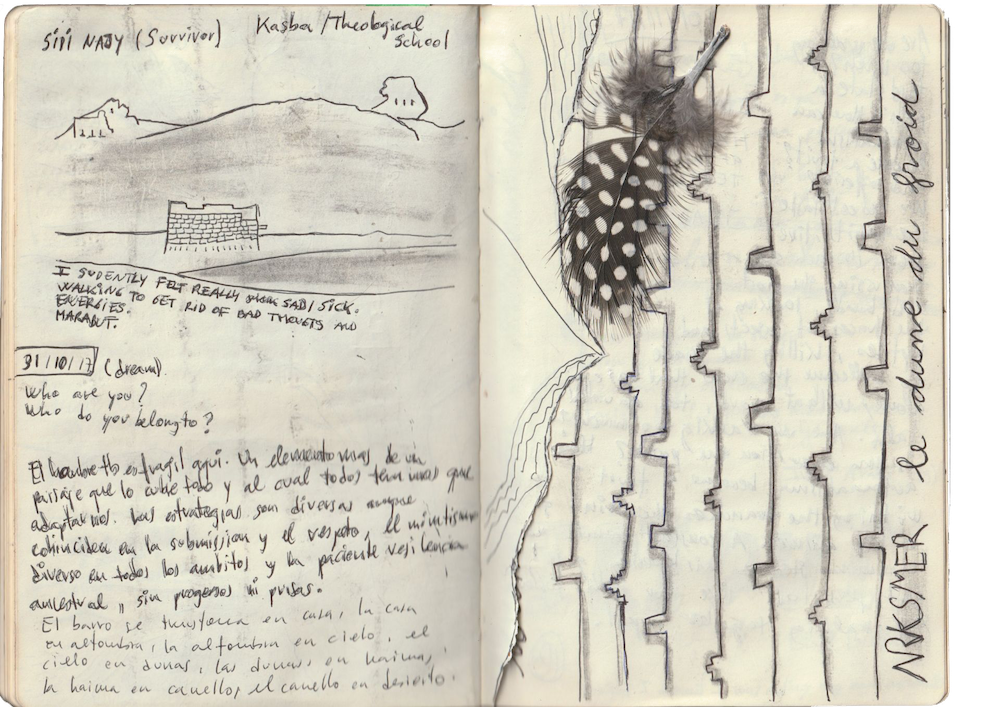

Man is also fragile here. One more element of a landscape that covers everything and to which we all have to adapt, temporarily or perpetually. However diverse they may be, strategies of adaptation share a common aspect of submission and respect towards that which is visible - but also to the invisible. These strategies are based on resilient and ancestral patience; they eschew both progress and hurry.

Sand is made into mud, mud into a house, the house into a carpet, the carpet into a starry sky, the starry sky into a sea of black rocks, the black rock into a camel, the camel into a haima, and the haima into golden dunes, sand, the desert.

![]()

November 1, 2017

Man is also fragile here. One more element of a landscape that covers everything and to which we all have to adapt, temporarily or perpetually. However diverse they may be, strategies of adaptation share a common aspect of submission and respect towards that which is visible - but also to the invisible. These strategies are based on resilient and ancestral patience; they eschew both progress and hurry.

Sand is made into mud, mud into a house, the house into a carpet, the carpet into a starry sky, the starry sky into a sea of black rocks, the black rock into a camel, the camel into a haima, and the haima into golden dunes, sand, the desert.

Southern moroccan desert,

November 3, 2017

Are we walking too much? How can suffering become fruit? Is this state a path? We indeed taste the limits, live them in each step, traversing arid lands, killing the snake to welcome the crow. Alone, without words, too exhausted to talk. Are we walking too much? How can suffering become fruit? Is exhaustion the path? Deep within the branches, the wind gives its silent answer: A constant warm whispering, quiet and persistent, following our walking together apart.

Southern moroccan desert,

November 4, 2017

The impossibility of perception is already a perception. The impossibility of perceiving the desert, this landscape, its components and functionings, is already a perception. The signs are to be found in its traces: the remaining fragments, the fragmented remains, its bones. The dried branches, big and small, growing from nowhere, everywhere, impossible to perceive, remain invisible beside their shadows: Thin black lines traced on the hot sand or the cracking land, forming new lives and phantasmagorias, move almost impossibly with the giant orbit of the sun, tracing daily circles, no one witnessing the lonely halaqahs.

Movement is perceived through its traces. Cockroaches, snakes, little birds and reptiles leave their testimony: an intricate, subtle, repetitive algorithm of life, impossible to perceive, erased every day through the persistent action of the Saharan winds that slowly displace the particles of sand, moving the vast dunes silently. And the skeletons, the fossils, the bones of millions of years of history and yesterday, half-buried or totally exposed, tell us about the fragility of life, of meteors, ancestors, and peoples, impossible to perceive.

November 4, 2017

The impossibility of perception is already a perception. The impossibility of perceiving the desert, this landscape, its components and functionings, is already a perception. The signs are to be found in its traces: the remaining fragments, the fragmented remains, its bones. The dried branches, big and small, growing from nowhere, everywhere, impossible to perceive, remain invisible beside their shadows: Thin black lines traced on the hot sand or the cracking land, forming new lives and phantasmagorias, move almost impossibly with the giant orbit of the sun, tracing daily circles, no one witnessing the lonely halaqahs.

Movement is perceived through its traces. Cockroaches, snakes, little birds and reptiles leave their testimony: an intricate, subtle, repetitive algorithm of life, impossible to perceive, erased every day through the persistent action of the Saharan winds that slowly displace the particles of sand, moving the vast dunes silently. And the skeletons, the fossils, the bones of millions of years of history and yesterday, half-buried or totally exposed, tell us about the fragility of life, of meteors, ancestors, and peoples, impossible to perceive.

Spring Sessions. Wonder, wander

(Amman)

Although the practice of the siyaha may seem to belong to a by-gone era, the tradition of vagabond hermits is still alive in the eastern Egyptian desert as well as in the Sinai peninsula. An example of the contemporary surge of interest in these practices can be found in The Heritage of the Desert Fathers, a project to map, photograph, and research hermitages and the tradition of wandering currently being led by the new Institute for the Study of Christian Tradition in Ljubljana, Slovenia. More relevant to this text, however, is the interest that has been shown in artistic and curatorial practices that investigate the space of the desert. Examples include Project Qafila, developed by architect and curator Carlos Perez; Cafe Tissardmine, founded by Karen Hadfield; and the project UNSCALE–Sahara, by AA Visiting School (AAVS) in London. In one way or another, by investigating the desert, all these projects pose a challenge to conventional ways of understanding the art residency model. Likewise, with its focus on experiential immersion into the desert through the practice of walking, the project Wonder, wander curated by Spring Sessions in Amman is an interesting case in point.

For its 2018 edition, Spring Sessions curated a nomadic residency program titled Wonder, wander. The project was loosely structured through a collective pilgrimage, starting from the northern tip of Jordan and ending in Sinai desert lands. Spanning a distance of more than 400 kilometres over the course of 6 weeks, the project engaged with the act of walking over a changing terrain. The aim was to contribute to the participants’ individual research and artistic practices while engaging with the transversal themes of journeying, premonition, foresight and pilgrimage.

For its 2018 edition, Spring Sessions curated a nomadic residency program titled Wonder, wander. The project was loosely structured through a collective pilgrimage, starting from the northern tip of Jordan and ending in Sinai desert lands. Spanning a distance of more than 400 kilometres over the course of 6 weeks, the project engaged with the act of walking over a changing terrain. The aim was to contribute to the participants’ individual research and artistic practices while engaging with the transversal themes of journeying, premonition, foresight and pilgrimage.

Spring Sessions

Spring Sessions is an experiential learning program and arts residency based in Amman, Jordan. The program creates a collaborative environment for artistic exchange between cultural practitioners. Conceived every spring as a program of workshops, mentoring sessions, research excursions, and other activities, their purpose is to question existing paradigms by experimenting outside of traditional modes of learning, while consciously engaging with several communities. Spring Sessions also has a permanent physical space, which includes: the makan makan makan, housing a darkroom; the ‘Lesser Amman Library;’ and a guest house for artists-in-residence. Spring Sessions [online] Available at: http://www.springsessions.org/?edition=edition2019-en [Accessed Day 16 June 2020].

Spring Sessions is an experiential learning program and arts residency based in Amman, Jordan. The program creates a collaborative environment for artistic exchange between cultural practitioners. Conceived every spring as a program of workshops, mentoring sessions, research excursions, and other activities, their purpose is to question existing paradigms by experimenting outside of traditional modes of learning, while consciously engaging with several communities. Spring Sessions also has a permanent physical space, which includes: the makan makan makan, housing a darkroom; the ‘Lesser Amman Library;’ and a guest house for artists-in-residence. Spring Sessions [online] Available at: http://www.springsessions.org/?edition=edition2019-en [Accessed Day 16 June 2020].