ريلكه

والحجاج

Rilke

and

the

pilgrims

The story of the Overcomers and the one of The Hidden sanctuary show artists, scholars and tourists complicity with Orientalist thinking and the tendency to idealise landscapes and local communities. This essentializing gaze is deeply resonant with another burgeoning phenomenon, quite in vogue at the same time in European artistic and literary circles: The art colony. Interestingly the art colony is understood in the established genealogy as the genesis of the history of the art residency, as so our proto-history of the Arab art residency ends where the official history currently starts.

Worpswede,

August 15, 1900

August 15, 1900

In August 1900, after a trip to Moscow and St. Petersburg, where he had been invited by Lou Andreas-Salomé, Rainer Maria Rilke arrived in Worpswede, a small village near the city of Bremen, at the core of the German Empire. Since 1889, Worpswede had become an artists' colony and several artists and writers had moved there in search of quiet, inspiration and intellectual challenges. Due to its cosmopolitan atmosphere, Worpswede became known as Weltdorf, the world village. Today, it is seen as the origin of the artist-in-residence phenomenon.

الحج

The Hajj

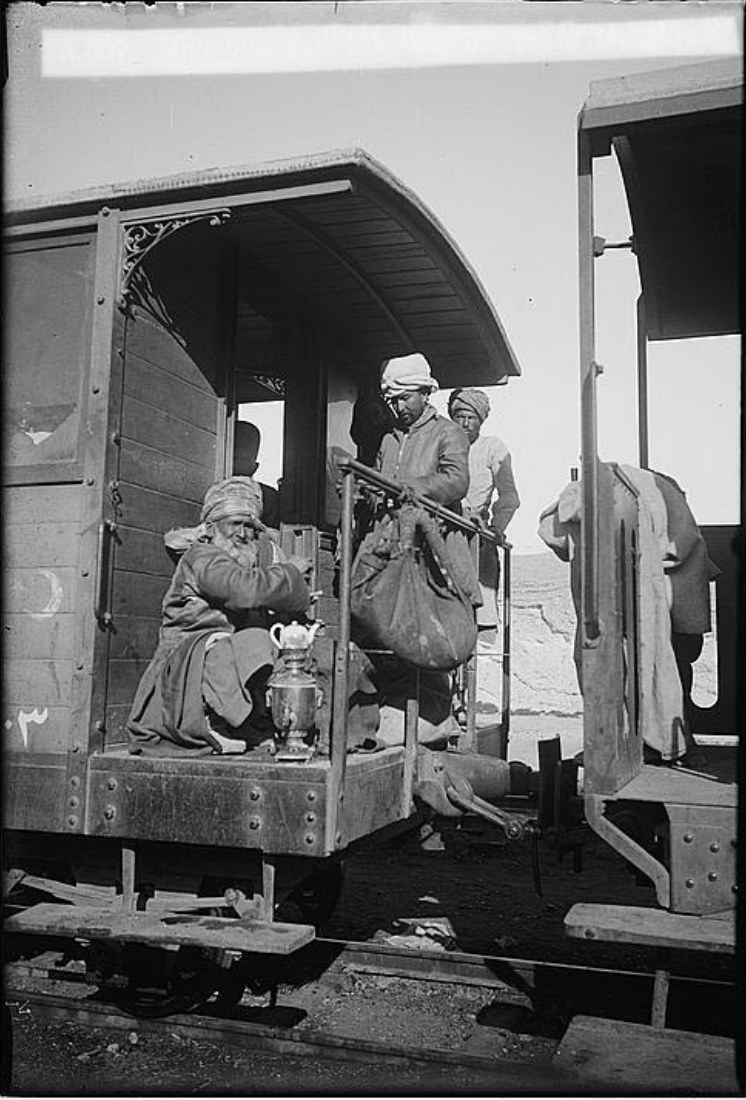

The 1900 marks also a fundamental change for the Hajj, the yearly pilgrimage to the sacred places of Islam: Medina and Mecca. Indeed that year the construction of the Hejaz Railway began in Damascus, at the behest of the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II. As part of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, financed by the Deutsche Bank and strongly supported by the German Empire, the Hejaz Railway was built to relieve the suffering of the pilgrims doing the Hajj from Damascus to Mecca by shortening the trip from 40 days to just four. The objective behind this generosity though was not Other than colonial expansion. The project represented a fundamental change to the Hajj and also marked an important shift in the practice of the rihla. Indeed, from then on modern transportation systems proved highly effective, supplanting the use of camels as a means of transport. Indeed, during medieval times, pilgrims would gather in the big cities of Syria, Egypt, and Iraq to go to Mecca in groups and caravans comprising tens of thousands of pilgrims, often under state patronage. Hajj caravans, particularly with the advent of the Mamluk Sultanate and its successor, the Ottoman Empire, were escorted by a military force accompanied by physicians. This was done to protect the caravan from Bedouin robbers or natural hazards, and to ensure that the pilgrims were supplied with the necessary provisions. In Islamic terminology, the Hajj is a pilgrimage made to the Kaaba, the 'House of God', in the sacred cities of Medina and Mecca in Saudi Arabia. It is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. The Hajj is a demonstration of the solidarity of the Muslim people, and their submission to God (Allah). The word Hajj means 'to attend a journey', which connotes both the outward act of a journey and the inward act of intentions. During Hajj, pilgrims join processions of millions of people, who simultaneously converge on Mecca and perform a series of rituals. Nowadays the Hajj has become a very lucrative industry that enlarges the Saudi economy by an estimated 16.5 billion Euros per year, representing about three percent of Saudi Arabia’s GDP. The average pilgrim pays around 4,500 Euros to cover the expenses of accommodation, airfare, food, and transport.As it can be read at El Kaiti, J Muslim Hajj: From Religious Ritual to Lucrative Business [online] Available at: https://insidearabia.com/muslim-hajj-religious-ritual-lucrative-business/#:~:text=Without%20a%20doubt%2C%20the%20Hajj,airfare%2C%20food%2C%20and%20transport. [Accessed Day 16 June 2020]. 'The association of 'Imams and Religious Leaders' in Tunisia released an unprecedented statement a few weeks ago calling upon Tunisians to boycott the pilgrimage, and urging would-be pilgrims to spend their money on disadvantaged groups and poor people in the country. The secretary general of the association, Fadil Achour, told Al-Jazeera.net that this call for a boycott comes in response to the high prices and rise in taxes by Saudi Arabia, which, according to him, 'spends Muslims’ money on wars against its neighbors rather than creating development opportunities.'This huge amount of money pumped annually into the Saudi treasury was repeatedly questioned by Muslims following the tragic stampedes of 1990, 1994, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004, and 2005 that claimed the lives of thousands of pilgrims. Downplaying these dramatic events, the number of Hajji continues to grow. The year 2012 marks the highest number of participants with over 3 million pilgrims. Besides the magnitude of these numbers what is of interest for this research project is the understanding of the Hajj as a practice from which the search for knowledge and the journey, and the act of gathering in one place for a week of rituals which often expands to a month — being that in Mecca, Medina or any Other of the sacred places of Islam, being that the tomb of a marabutA marabout is a Muslim religious leader and teacher in West Africa, and historically in the Maghreb. The marabout is often a scholar of the Qur'an, or religious teacher. Others may be wandering holy men who survive on alms, Sufi guides, or leaders of religious communities. or a shrine — resonate with the act of gathering and exchange performed by researchers and artists alike within the expanding context of contemporary art residencies. As Waenerberg (2005) points out 'Naturally, the motives of individual pilgrims may have been sincerely virtuous, but observed as a ‘system of rituals’, the piety of pilgrims can easily appear as self-righteousness or a need to slavishly observe a behaviour model. In this way, the redemption or salvation of the soul by means of a ritual can take on completely contradictory meanings. The Same is true of an artist’s trip to Paris. Pilgrims were bound through solidarity towards brOthers and sisters sharing their vocation, while locals were bound through benevolence towards pilgrims, which usually took the form of ‘organizing’ benevolence, i.e. lodgings and places to eat. Solidarity was also evident among artists; a place to spend the night could always be arranged for a fellow-artist needing shelter. Local residents had no intention or obligation to allow artists to become full members of their community, but it was always good to tolerate them'. (Waenerberg 2005. p.5). What might it mean to think about art residences and the Hajj together? Which are the epistemological resonances that could interlink these two apparently disconnected realities? And what is to be learned from the articulation of critical genealogies as a method of inquiry?

Art & Colonies

الفن والمستعمرات

As Rilke’s story suggests, the search for the marvelous and the unfamiliar in Ömer Seyfeddin's fascinating story was not unique to the pilgrims, pseudo-explorers and artists who travelled to the Holy land, Istanbul or the desert oasis. It was in fact the common zeitgeist of romantic travellers and artists throughout Europe as well. From the 19th century onwards, Western artists celebrated the Other at home by imitating Oriental decorative styles and design motifs in their creations. In these pieces, they were always sure to include romanticised, dreamlike renderings of the lands and peoples of the East. In similar fashion, certain Romantic painters, without ever having travelled abroad, painted Orientalist scenes of great sensuality, endowing the colonial East with erotic and exotic difference. The spread of art colonies, which is seen nowadays as the origin of the art residency global phenomenon, is deeply related to these Orientalist and romantic processes of Othering within Europe.

By the mid - 19th century, Northern European artists' attention had shifted from portraits of their wealthy patrons to still life, self-portraiture and landscape painting. The effects of industrial production had huge consequences on this process. In the case of canvas painting,

It is in this context that art colonies arose in Europe as the ultimate, utopic space and place in which to gather, discuss and create. As we can read in Nina Lubbren’s study Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe 1870–1910, between 1830 and 1910 more than 3000 self-styled artists went to live in dedicated colonies. By the 1900s, there were more than 80 such colonies firmly established around the continent. As Lubbren states,

The organic village life and idealised landscapes these artists painted and wrote about was

'whereas artists of the past centuries had had to produce their own paints, laboriously mixing ingredients, now paint became newly available in tubes for the first time, as did lightweight portable easels. This environment produced an entirely new way of painting, which came to be known as en plein air. Across Europe, painters packed up their foldable easels and boxed sets of factory-made paints and brushes and trekked out into the continent's pastoral landscapes to paint nature in all its glory.'

It is in this context that art colonies arose in Europe as the ultimate, utopic space and place in which to gather, discuss and create. As we can read in Nina Lubbren’s study Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe 1870–1910, between 1830 and 1910 more than 3000 self-styled artists went to live in dedicated colonies. By the 1900s, there were more than 80 such colonies firmly established around the continent. As Lubbren states,

‘The majority of these colonies gravitated towards the Baltic and Celtic fringes rather than the Mediterranean; for unlike many nineteenth-century poets who dreamed of a beaker full of the warm South, the new enthusiasm among painters and writers alike was for unpopulated flat moorlands, chilly streams and lakes, idealised coastal villages and vast open skies.'

The organic village life and idealised landscapes these artists painted and wrote about was

'a benign but deeply unrealistic construct, juxtaposing elements from various periods and different local cultures in order to achieve an integrated and organic whole. The railway trains which brought them to these remote places were never included in their mise-en-scène, neither were the large bourgeois villas, the telegraph lines, nor any of the local industries which might disturb the image of rural economic primitivism which the villagers themselves were keen to escape.'

Much like in Orientalist paintings and texts, in narratives that depicted rural European art colonies, human presence was either marginal or fictionalised. Instead, the viewer’s or reader’s eyes were guided to the romanticised landscapes or fictionalised local life. To the discerning eye, the potentials of the future were predicated on absences. Likewise, as scientific expeditions to the colonies began to multiply, the figure of the benign, literate and innocent scientist so too emerged. The act of discovery, for which so many untold lives had been sacrificed and countless miseries endured, was represented in European metropolitan visual culture as a purely passive experience, that of seeing. As Pratt argues,

this particular way of seeing was imposed through the 'authority of Europe’s mastering discourses, which claim to wish to see and wish to know, but which only see what they wish to see and know what they wish to know.'

Interestingly the spread of art colonies in Europe took place at the same time as European colonisation in Africa and Asia. Indeed, amongst the many stories that are being neglected in the history of art residencies, the one of how art colonies’ heydays coincided with the period of colonial expansion is nowhere to be seen. In sharp contrast with this account, which seeks to link art colonies’ global expansion and the expansion of colonial powers worldwide, the official history of art residencies states that,

'in the 1990s, an enormous wave of new art residency initiatives proliferated, no longer confined to the Western world but spread all over the globe. Residential art centres, especially in non-western countries, function more and more as catalysts in the local contemporary art scene and have become indispensable for connecting the local scene with the global art world.’

This account of the journey between the Same and the Other, framed by the encounter with the marvelous and the unfamiliar in non-Western lands, neglects the fact that these journeys have been enjoyed for the most part by Western and Westernised creative individuals, who, like their counterparts in the mid - 19th century, often claim to represent non-interventionist European presence and an innocent pursuit of knowledge. In Rooted and Slow Institutions Reside in Remote Places (2019), Vytautas Michelkevičius states that

'If one wishes to look critically at artist-hosting, residencies also serve as a new type of soft colonialism (...) Some of the residencies exploit the place and its resources for the sake of the ones in power or with knowledge. This happens quite often when artists embark on residential trips outside of the so-called West in search of the exoticism and some wilderness, chaotic everydayness and sometimes sincerity and hospitality of a small place'

Michelkevičius sentences 'International residency programmes help to

‘normalise’ this while including these countries and their specific places with their resources into the international flows of value.’

As it happened to travelers in the Holy Land or at the Sublime Porte, it is not infrequent that travelling artists' expectations are met with certain disappointment, as what is desired is not always found. And so, art residency hosts in rural contexts or remote locales often find themselves playing the (unconscious) game of self-Othering through exoticism: that is, they construct a narrative in which the need for the gharib al-lugha, the ‘rare and obscure,’ or for that matter the folkloric or indigenous, continues to be performed.