جان ، إسماعيل

والنساء الأمازيغ

Jan, Ismāʿīl and

the Amazigh women

Jan, Ismāʿīl and the Amazigh women is a commissioned text for the project The unreal carpet. The text proposes a fictional conversation between the protagonists of the project:

The engraver Jan Luyken; Moulay Ismail ibn Sharif, Sultan of Morocco; and a group of Berber women from the Yagour cooperative in Tighdouine.

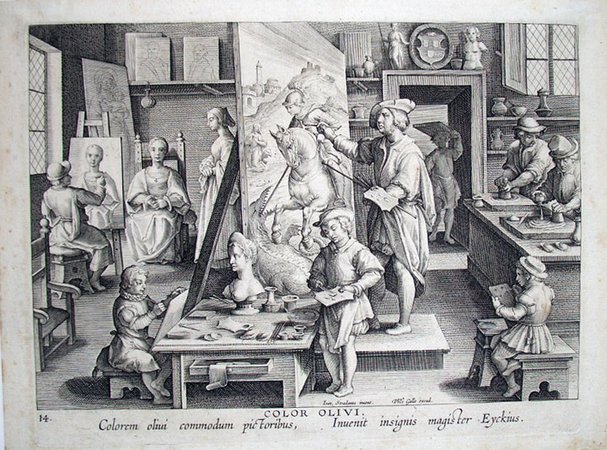

Several decades after the death of al-Maḳḳarī in Cairo, we meet Jan Luyken in his Amsterdam studio. Lost in his thoughts, he is working on quite an astonishing piece: an engraving of a highly unrealistic and exoticised scene representing 17th - century Morocco

Amsterdam,

February 15, 1686

February 15, 1686

It is a rainy and cold day in Amsterdam. Europe is reeling from an era of turmoil, after a century of religious wars. The dark times of fratricidal battle have finally concluded thanks to the Peace of Westphalia. The newly-formed Dutch Republic has been liberated from the corrupt Spanish crown. The arrival of skilled workers, including Sephardic Jews and Huguenots, combined with the expansion of the protestant work ethic and the birth of corporate finance, have made the Netherlands a global economic and cultural power.

Meknes,

February 15, 1686

February 15, 1686

It is a foggy and warm day in Meknes, and for once the young Ismāʿīl ibn Sharīf is in a good mood. The massive construction works in the new capital of the Moroccan kingdom are advancing at a good pace, the enclave of Al-Maʿmūrah and the city of Tangiers, both in English hands, have been re-conquered, and the battles against the Ottomans’ allies in Algiers have been a success. The consolidation of the Alawï dynasty has been completed, through the internal pacification of Morocco, and the long, prolific and cruel reign of the Alawī dynasty has been secured under the despotic orders of Ismāʿīl. The new Sultan has finally outsmarted Ahmad al-Mansur who, a century earlier, transformed the Moroccan Sultanate into one of the most powerful empires of the region.

Amsterdam,

February 15, 1686

February 15, 1686

It is a rainy and cold day in the prosperous Dutch capital and Jan Luyken continues to patiently work on his copper etchings, by the weak glow of a gaslight. He is in his studio, surrounded by several printing plates, burins and gravers. Jan feels particularly content today, as he can fully dedicate himself to the task of finishing a rare and precious piece: Marroco. As an educated and cultured man, Jan is not impermeable to the new power of the Dutch Republic. He has never been to Morocco and has no intention to go. Nevertheless, when he looks at Marocco, he feels proud to be contributing to the international influence of his beloved Golden Republic.

Meknes,

February 15, 1686

February 15, 1686

It is a foggy and warm day in the new capital of Morocco, and for once Ismāʿīl ibn Sharīf is in a good mood. His army of dark-skinned Saharan slaves, the Abid al-Bukhari, is admired beyond its territories and Ismāʿīl has secured the necessary revenues for his public works. In effect, he holds a monopoly on foreign trade. The palace of Meknes, styled on the palace of Louis 16th in Versailles, is a massive monument to Ismāʿīl’s will and determination. It is also a golden prison for his four wives and 500 concubines.

Tighdouine / Marrakech,

February 15, 2016

February 15, 2016

It is a sunny and fresh day in Tighdouine. Still hidden in the Atlas mountains, the town awakes to the whispering river and the deep green of the oaks and olive trees that cover the fertile Zat valley. A group of Amazigh women gather around a loom. Since ancient times, Berber weaving has relied on female culture, making its way through generations of women through traditional teachings on different looping techniques, patterns, colours and mystic symbolism. In this humble society, wool itself has special protective powers. The women, reunited in the workshop, look in astonishment at Marocco etching. Ahead of them, there is a long month of patient weaving in red and black wool, as they will slowly trace the design made by a Dutch engraver named Jan Luyken in his poorly illuminated studio 350 years prior. For the next weeks, they will transfer to their beloved wool the creation of a man who, on a cold and rainy morning in the Dutch Golden Age, imagined the peoples of Morocco as the sons and daughters of Ismāʿīl’s black slave army and 500 concubines.

'It looks like the man is a threat to the woman, but she is full of dignity and does not pay attention to him' says Aicha, 'Even if he treats her, she will do whatever she wants to do.'

'It looks like the man is a threat to the woman, but she is full of dignity and does not pay attention to him' says Aicha, 'Even if he treats her, she will do whatever she wants to do.'

The group of Amazigh women look at each other assertively. From that moment on, they will meet each afternoon, handling the thread with dignity, doing what they want to do, together: to fight, step by step through each knot, around the loom. From their perch overlooking the fertile Zat valley, accompanied by the whispering river and the deep green of the oaks and olive trees, they will weave together. The still-unreal carpet will materialise in the gentle hands of the women of Tighdouine.

It is evening, and the Amazigh women in Tighdouine go back to their houses, slowly, step by step, still chatting. The singing swallows announce the spring through the narrow village streets. Some 60 kilometres away, they can also be heard through the busy alleys of Marrakech medina. We are at Ke’cH Collective. Jan Luyken’s Marocco etching has been transformed into a red and black carpet. A mirror hangs from the ceiling and it is then when the unreal happens. The image of two fantastic characters made to represent Morocco duplicates in a game of reflection where the viewer, confronted with his own image, also becomes a central piece. The anachronism of symbolic layers is mesmerizing.

Jan, Ismāʿīl, a slave and a concubine. The golden age of knowledge and cruelty … and them: Their voices resonate in the intimate space, their humble reflections become a chant, like the singing swallows, the constant fight for recognition, traversing centuries through the streets of Amsterdam, Meknes, Tighdouine and finally Marrakech, creating a nest of comforting empathy.

'I think they should be the same', says Faouzia.

We should all agree.

'I think they should be the same', says Faouzia.

We should all agree.

Ke’cH Collective’s

‘Laboratoire de la Mondialité’

(Marrakesh)

In the framework of the 6th Marrakech Biennale, Ke’cH Collective proposed the project ‘Laboratoire de la Mondialité:’ a full program of residencies and exchanges, through which artists from Morocco and Switzerland would work in collaboration on several artistic research projects. These creative exchanges focused on the multiple, and too often misleading, representations of European and Arab identities.

It was in this context that the artists and curators Abdelaziz Zerrou and Aglaia Haritz proposed The unreal carpetThe unreal carpet is part of the larger project Embroiderers of Actuality a long term initiative, which was developed beginning in 2013 by Abdelaziz Zerrou and Aglaia Haritz through different art residencies and public presentations in Cairo, Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakech and Beirut. The Unreal Carpet, Embroiderers of actuality [online] Available at: http://embroiderers-of-actuality.com/portfolio/unreal-carpet-wool-handmade-carpet-260x2m-2016/ [Accessed Day 16 June 2020]. a project that would see Jan Luyken’s 17th - century engraving of Ismāʿīl ibn Sharīf’s Morocco transformed into a carpet made by a group of Berber women from the Yagour cooperative in Tighdouine. Linking the practices that shape everyday life and historical grand narratives, The unreal carpet organically wove unexpected links between distorted 17th - century imaginaries and 21st - century micro-feminisms. Moving away from confrontational attitudes and sterile dualisms, the project adopted an unconventional approach to discussing topics such as the relationship between craft and activism, the power of cross-cultural reflection, the dislocation of historical artifacts and the relationship between fictional realities. The project imagined possible futures by enhancing the power of the Amazigh women to promote and demand equality through empathy, resilience and the patient art of carpet-making.

It was in this context that the artists and curators Abdelaziz Zerrou and Aglaia Haritz proposed The unreal carpetThe unreal carpet is part of the larger project Embroiderers of Actuality a long term initiative, which was developed beginning in 2013 by Abdelaziz Zerrou and Aglaia Haritz through different art residencies and public presentations in Cairo, Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakech and Beirut. The Unreal Carpet, Embroiderers of actuality [online] Available at: http://embroiderers-of-actuality.com/portfolio/unreal-carpet-wool-handmade-carpet-260x2m-2016/ [Accessed Day 16 June 2020]. a project that would see Jan Luyken’s 17th - century engraving of Ismāʿīl ibn Sharīf’s Morocco transformed into a carpet made by a group of Berber women from the Yagour cooperative in Tighdouine. Linking the practices that shape everyday life and historical grand narratives, The unreal carpet organically wove unexpected links between distorted 17th - century imaginaries and 21st - century micro-feminisms. Moving away from confrontational attitudes and sterile dualisms, the project adopted an unconventional approach to discussing topics such as the relationship between craft and activism, the power of cross-cultural reflection, the dislocation of historical artifacts and the relationship between fictional realities. The project imagined possible futures by enhancing the power of the Amazigh women to promote and demand equality through empathy, resilience and the patient art of carpet-making.

Ke’cH Collective was founded in 2015 in Marrakech by a group of cultural actors from Morocco and Switzerland. Its mission was to empower creatives and to encourage cross-cultural exchange and interaction in order to preserve and highlight diversity. The short-lived project was based in an abandoned house at the entrance of the medina.

On the pre-studio condition

مرحلة ما قبل الاستوديو

Even as majālis and halafāts were developing as loci of creative and collaborative encounters throughout the Arab lands, another space of artistic creation was arising in Europe. This is none other than the studio. In Time and Space to Create and to Be Human. A Brief Chronotope of Residencies (2019), Pascal Gielen describes the studio as

'[a] sheltered space of highest concentration, focus, quiet, contemplation, and being intimate with oneself. In the studio, the artist is completely in control, still experiencing the romantic illusion of artistic autonomy at its best. Studio time is therefore personal ‘own-time’ and studio space the ‘own-space’ (...) No words are uttered in the studio, at most some incomprehensible muttering and mumbling, alternated by an exuberantly joyful cry as something finally seems to be working out.'

The studio model first emerged in the 17th century in northern Europe. Wishing to escape from the constraints of religious guidance, private individuals imposed themselves as arbiters of taste and patrons of the arts. In doing so, the nascent industrious bourgeoisie supplanted the centralised infrastructure of the Church, which had dominated the production of art in the European Middle Ages. Nevertheless, the break with religious tradition was not as obvious as it could be: as Brian O’Doherty has argued,

In line with the sacralised conception of the artwork, another aspect remained untouched: seclusion continued to be a necessary precondition for the novel studio practice. Indeed, the history of the studio as a chamber of eternal creation and display can be inscribed not only in the history of art but also in the history of religion. Similarly to the work of scholars and pious men, the practice of studio art is also geared towards the attainment of a higher metaphysical realm. As such, the studio space had to be sheltered from time and the appearance of change. The studio thus became a reflexive space, with the act of contemplation becoming incorporated into the creative process. Indeed, important developments in oil painting techniques allowed for the careful and hyper-realistic depiction of everyday objects over a slow, drawn-out process of mixing, layering and drying. This process required patience and dedication, silence and careful contemplation, the painting becoming in itself, an object of cult, a

'the purpose of the studio was not unlike that of the religious buildings. The artworks, like religious verities, had to appear untouched by time and its vicissitudes.'

In line with the sacralised conception of the artwork, another aspect remained untouched: seclusion continued to be a necessary precondition for the novel studio practice. Indeed, the history of the studio as a chamber of eternal creation and display can be inscribed not only in the history of art but also in the history of religion. Similarly to the work of scholars and pious men, the practice of studio art is also geared towards the attainment of a higher metaphysical realm. As such, the studio space had to be sheltered from time and the appearance of change. The studio thus became a reflexive space, with the act of contemplation becoming incorporated into the creative process. Indeed, important developments in oil painting techniques allowed for the careful and hyper-realistic depiction of everyday objects over a slow, drawn-out process of mixing, layering and drying. This process required patience and dedication, silence and careful contemplation, the painting becoming in itself, an object of cult, a

'slender and reduced form of life required also in religious Sanctuaries.'It was in these secluded spaces that a new form of framing the individual act of creation and the production of aesthetic knowledge slowly arose. It was also there that the high culture of Modernity became subject to the universalising regime of formalism as a system of reading. The self-fashioning of the artist as genius, together with the growing penchant for formalism, altered the status of the artwork profoundly. Indeed, while it continued to be seen as a privileged commodity fetish and an object of connoisseurship, it was gradually reduced to its physical qualities and so reframed in semantic poverty.

Although the emergence of the studio as a space of isolated artistic production is considered a breakthrough in Western art history, and is even seen in many narratives as the origin of contemporary art practices, the history that follows is by no means straightforward.

︎︎︎Even though the Romantic idea of the artist has significantly eroded, the studio continues to function as a hermit-like space. It is no coincidence that quite a number of art residencies are located in the middle of nowhere, far from all urban confusion, away not only from the professional art world, but from the world itself. In this way, they can be seen to replicate the studio episteme.

Indeed, since the turn of the 20th century and the emergence of the avant-gardes, the studio has undergone a series of crises. As artists have come to embrace installation art, performance, relational aesthetics and other site-specific approaches that necessarily occur outside of the studio, this site of solitary creativity and material exploration has become a social space. In this context we are in need of posing the following question: What if the contemporary surge of networked, collaborative and socially engaged practices had more to do with those performed within majālis, coffee-houses and ḥafalāts rather than with a natural evolution of the studio space? If we look at the history of such practices not as a linear path but as an interconnected organism, free of temporal or spatial boundaries, could we consider majālis, coffee-houses and ḥafalāts as part of a pre- and the post-studio condition? Such a proposition would bring into focus the spaces of gathering and encounter that ground artistic creation. It would bring us to contemplate the possibility of tracing an alternative genealogy, one that does not excessively focus on the production of art objects but rather pays attention to the practice of the journey as a search for knowledge. What if the experimental modes proposed from within the contemporary art residency models had more to do with the need to gather around a table at a coffee-house in 17th - century Cairo than with a sojourn at the studios of the elitist French Academy in Rome? What if the collaborative task of Islamic men of letters gathered around the fire translating and discussing texts on cosmology, geography and mysticism as part of a week-long ḥafalāt was also taken into account when tracing other histories of the art residency? And, moving a step further, what if, as Wendy M.K. Shaw has proposed in her writings on Islamic art history, we rethink the genealogy of art residencies by placing not artistic production but the heart at the centre? Too often, within the art residency field, it is the I who speaks, not the we. As Pascal Gielen has noted,

it is within this I, self-enclosed in the confines of the studio, that 'the endless ambition of the artists continues to flourish.'

Thinking about the strategies of creation and exchange in medieval and modern Arab territories through the majālis, coffee-houses and ḥafalāts may indeed open new avenues to understanding the creative act — not so much as an individual, isolated practice, but as a collaborative and trans-disciplinary endeavour.