Conclusion?

Keep Walking

إلى الأمام

While accompanying Rilke to Wospede and the Hajjis to the Kabba, the speculative proto-history of the Arab art residency we have gone through ends where the official one starts. Before abandoning our companions to their intertwining destinies though, a last reflection needs to be made. To do so we will go back to where we started: the desert.

One Single Eye

عين واحدة

︎︎︎One Single Eye is a self-reflexive account of my experience during a two-week research retreat at Les Glycines (Algiers) and at the CCDS : Centre Culturel et de documentation Saharienne (Ghardaïa, South Algeria) during February 2017. This research expedition was funded by the University of Edinburgh ‘Principal’s Go Abroad’ Fund. In retrospect, this account is seen as yet another example of how the unknown, the ‘rare and obscure’, continues to be fundamentally present, while demonstrating how the fragile condition of knowledge constructed on the journey between the same and the other persists.

Les Glycines, Algiers,

February 2, 2017

February 2, 2017

︎︎︎Founded in 1966 at the initiative of Cardinal Léon-Etienne Duval, Archbishop of Algiers, Les Glycines Centre d'études diocésain originally trained personnel within the Church of Algeria, and prepared them for the linguistic, social, cultural and religious realities of a young, independent Algeria. The center, established by Henri Teissier and Pierre Claverie, was supported by requirements set by the Second Vatican Council, which committed the Catholic Church to be in solidarity with the human and cultural environments. In particular, the Church was interested in Islam, not for the purposes of proselytism, but to appreciate the Muslim tradition in its spiritual and religious dimensions. It is in this spirit that the Centre of Studies provides training in Islamic Studies and promotes inter-faith dialogue since 1970. Since 1973 Les Glycines has had a research library bringing together various private funds established during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The library’s collections comprise unique research materials on linguistics and Maghrib Arabic and Amazigh dialects and literatures, anthropology, ethnography, geography and cartography, archaeology, architecture and Maghreb literature in both Arabic and French. The library includes about 90,000 records and more than 1,100 titles of journals and periodicals. Besides other activities like Arabic language courses and The University for All, Les Glycines works also as a residency for artists and researchers in the humanities and the Social Sciences. The residents have full access to the library and archive as well as to the studio and garden. The community of researchers gathers at meal times.

Not far from where I am - sitting in front of a small brown table in a monastery-like room with a window overlooking the Embassies and the cold day of an almost attractive Algiers - there is the archive; and a group of old men, deep connoisseurs of so much, drinking coffee.

The subtle connection, framed by an austere and insufficient meal (as recommended by The Book) has been almost instant.

While walking through the absurd tasks and my worries, whispering, He soon knew me.

This He is an 80 years old man, white-collar, green eyes, almost transparent.

Looking at me, towards an indefinable somewhere, his words were like the desert he was telling me about: Humble, exact, conformed by the intensity of the silences and the no-times.

— You should go to Ghardaïa. He said,

A few hours later, between the sunset of Hypnos and the new day, a storm.

The subtle connection, framed by an austere and insufficient meal (as recommended by The Book) has been almost instant.

While walking through the absurd tasks and my worries, whispering, He soon knew me.

This He is an 80 years old man, white-collar, green eyes, almost transparent.

︎︎︎I later learned that the man was Henri Teissier, Bishop of Oran, Archbishop of Algiers, awarded with the Légion d'Honneur for his ecumenical work inspiring the dialogue between Christianity and Islam.

Looking at me, towards an indefinable somewhere, his words were like the desert he was telling me about: Humble, exact, conformed by the intensity of the silences and the no-times.

— You should go to Ghardaïa. He said,

A few hours later, between the sunset of Hypnos and the new day, a storm.

CCDS, Ghardaïa,

February 17, 2017

February 17, 2017

︎︎︎CCDS ︎︎︎ The presence of the White Fathers in Gardaïa dates back to 1884. With the White Sisters and a few lay people, they form the small multinational parish community. The White Fathers community went from 4 to 6 members in March 2016. Apart from other activities such as visit to Sub-Saharan Migrants and to the center for the disabled in Touzouz, they try to be a bridge between the different populations. This is done through the CCDS - Center Culturel et de Documentation Saharienne. The CCDS offer support courses, in French, English, and German, and many other activities such as photo exhibitions, conferences and cultural or study days. The center also has a research and learning library with valuable documents including a collection of maps, travel-journals and expert literature on anthropology, sociology and architecture from the region as well as a huge photo archive with valuable documentation dating back to the White Fathers’ first expeditions in the region. The center also hosts religious men and researchers in residence

︎︎︎Ghardaïa is part of a pentapolis, a hilltop city amongst four others, built almost a thousand years ago in the M’Zab Valley, in southern Algeria. It was founded by the Berbers Moabites, an Ibadi sect of non-Arabic Muslims. The original architecture of the semi-desert valley dates back to the 11th century when villages were fortified in such a manner that they were inaccessible to the nomadic Arab tribes.

After a ten hours bus trip down south, I finally arrived in Ghardaïa. Slept in a humble room and a quite basic bed provided as part of the residency for researchers run by the small community of Pères Blancs.

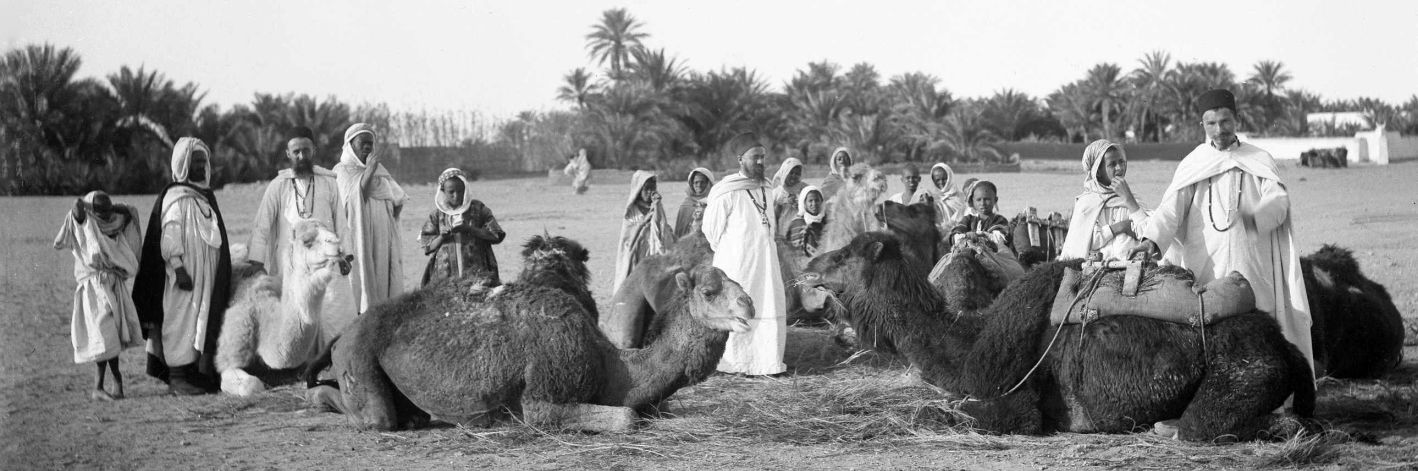

The next day I spent it at the CCDS - Centre Culturel et de Documentation Saharienne fascinated, some would say in a pseudo-colonial way, by the diaries and accounts of pilgrims and adventurers that, from the start of the 19th century, hosted here by the small community of Pères Blancs, retraced the ancient trans-Saharan routes driven like me by curiosity, ingenuity and an orientalizing gaze.

︎︎︎The 'Pères Blancs'' or the Missionaries of our Lady of Africa of Algeria are defined in 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia as follows: ‘This society, known under the name of 'Pères Blancs' or 'White Fathers', was founded in 1868 by the first Archbishop of Algiers, later Cardinal Lavigerie. The famine of 1867 left a large number of Arab orphans, and the education and Christian instruction of these children was the occasion of the founding of the society; from its inception the founder had in mind the conversion of the Arabs and negroes of Central Africa. Missionary posts were established in Kabylic, Gardaïa and in the Sahara. In 1876 and in 1881 two caravans from South Algeria and R'dames, intending to open missions in Sudan, were massacred by their guides. In 1878 ten missionaries left Algiers to establish posts at Lakes Victoria Nyanza and Tanganyika (…) The costume of the missionaries resembles the white robes of the Algerian Arabs and consists of a cassock or gandoura, and a mantle or burnous. A rosary and cross are worn around the neck in imitation of the mesbaha of the marabouts. The society depends directly on the Congregation of Propaganda. The White Fathers succeeded in establishing small missions among the Berbers of Jurjura (Algeria), there being at present nine hundred and sixty-two Christians. To religious instruction the missionaries add lessons in reading and writing, and teach also, in special classes, the tongue of the European nation governing the country’ in the New Advent.

The next day I spent it at the CCDS - Centre Culturel et de Documentation Saharienne fascinated, some would say in a pseudo-colonial way, by the diaries and accounts of pilgrims and adventurers that, from the start of the 19th century, hosted here by the small community of Pères Blancs, retraced the ancient trans-Saharan routes driven like me by curiosity, ingenuity and an orientalizing gaze.

The evening falls, it will be a cold and dark night. We are four on the old car that is slowly climbing the hill when I ask one of the Pères Blancs about what seemed to be a slump I saw on my afternoon walk.

Besides the Moabite woman dressed in their white haiks and showing only one single eye, what caught my attention are also a few black youngsters keeping themselves busy, arranging shoes, and the black women wrapped in colourful dresses on the corners of the narrow streets, begging. But what has surprised me the most has been to find what seems to be their provisional homes: a camp built with wood, plastic and all kinds of debris half hidden outside the ancient defensive walls, between the cemetery and what is now a dry river populated by plastic bags.

He answered:

— They are the Nigerians. They come from Uyo and Owerri escaping from scarcity after the war.

In 2014 the Algerian authorities realised a new law forbidding the access of Nigerians without valid passports to the regular buses that depart from Tamanrasset, at the border with Niger towards the North, to Ghardaïa and Algiers. If Ghardaïa is known as the door to the Saharan desert, Tamanrasset, a city 2000 km further south, is in the middle of it.

For what I saw, the governmental measures didn't succeed in stopping the migration of Nigerians towards the North. Instead of using the bus though,

now they are forced to look for alternative routes provided by the smugglers of migrants, which do the job at unaffordable prices and take vulnerability as an exchange rate.

The community of Nigerians in Ghardaïa is formed by three different groups:

The first one, which is a minority, used to be blacksmiths back home, and thanks to their skills, have become either shoe-makers or workers on building sites where some also live. The building industry in Ghardaïa is prosperous as in recent years there has been an important flux of Arabs moving into the city, changing the status quo and the predominance of Moabites, the original settlers. The second group are women, children and elders, and they usually beg in the dusty streets around the market. And the third group is conformed by young boys and men that have become some kind of an alternative health system. Besides selling all sorts of advice and herbs, they also provide aphrodisiacs for the local sexually handicapped. All of them find in Ghardaïa the exit door from the desert becoming though the lower social class in a rigid system of a community mainly formed by the old Berber Moabites and the Arab Chaamra, also newcomers that slowly are colonising the newly built suburbs. The relationship between the Moabites and the Chaamra are far from being fruitful. Since the discovery of petrol in the late 1950s, the population of the region has been substantially altered. The area has also been destabilised by external actors linked to economic interests and an increase in illegal trafficking.

In 2015 riots erupted in the mud made city, causing great distress, destruction and 22 casualties. Since then, the population shares the public space with the army: Overprotected with guns, shields and military clothes 10.000 young Algerians arranged in groups of three or four spend their time browsing their phones and sipping mint tea.

I look through the window. Ghardaia slowly changes again and amused, incapable to process,

I think back to my curiosity, that ingenuity and still unavoidable orientalizing gaze.

حراڨة

Harraga

On the journey between the Same and the Other, the Harraga is a fundamental practice that adds further complexity to the relationship between the search for knowledge and the journey within Arab and Islamic epistemologies. This proto-history of the Arab art residency will end by suggesting that, as in the case of the several models proposed, the Harraga can become also relevant to speculate on several of the complications affecting the field of contemporary art residencies while at the same time enhancing further exploration.

The tolerance and hospitality experienced by pilgrims performing the Hajj and artists within art colonies is nowhere to be seen in the experience of those that, at the turn of the 21st century, and due to economical, political or cultural hardships have no other option than escaping to other lands. The Algerian Arabic word harraga — the action of burning the borders and the sea — designates those who burn their passports and seek fortune in Europe. As we can read in Turkey's Brain Drain: Why Youths See No Future There by Burak Bekdil 'In just the first 65 days of the C-19 pandemic, 510 Turks were arrested for spreading baseless and provocative messages in social media. Before that, by the end of 2019, Turkey had banned access to 408,494 web sites, 7,000 Twitter accounts, 40,000 tweets, 10,000 YouTube videos and 6,200 Facebook accounts'.

As we can read in Bekdil’s article 'there is new data suggesting that younger Turks have a Western mindset instead of 'religiously conservative/devout' one, as Erdoğan hoped they would. This is in sharp contrast with the official teachings of a country where the top Islamic cleric said that 'children who do not read the Quran are with Satan and Satanic people.'

The situation in the most populated country in the region, Egypt, is far from being any better. Following a brief opening after the 2011 revolution, Egypt’s independent civil society organizations today face the most repressive environment in decades. Historically, autocratic governments in Egypt have selectively used civil society restrictions to ensure civic mobilization did not cross the ruling regime’s red lines. In contrast, Egypt’s new military government is using a multitude of tactics to undertake a much more comprehensive campaign to shrink civic space. Indeed, adding to the many cultural and political activists taken to prison with no clear charges, several cultural organizations have had to close their doors, amongst them two of the main artistic spaces of the country: Gudarn and Townhouse. Looking for an escape from this repression most activists, artists, researchers and curators have tried their luck in Europe, transforming one of its more dynamic urbes, Berlin, in the capital city of Arab exile.

The tolerance and hospitality experienced by pilgrims performing the Hajj and artists within art colonies is nowhere to be seen in the experience of those that, at the turn of the 21st century, and due to economical, political or cultural hardships have no other option than escaping to other lands. The Algerian Arabic word harraga — the action of burning the borders and the sea — designates those who burn their passports and seek fortune in Europe. As we can read in Turkey's Brain Drain: Why Youths See No Future There by Burak Bekdil 'In just the first 65 days of the C-19 pandemic, 510 Turks were arrested for spreading baseless and provocative messages in social media. Before that, by the end of 2019, Turkey had banned access to 408,494 web sites, 7,000 Twitter accounts, 40,000 tweets, 10,000 YouTube videos and 6,200 Facebook accounts'.

As we can read in Bekdil’s article 'there is new data suggesting that younger Turks have a Western mindset instead of 'religiously conservative/devout' one, as Erdoğan hoped they would. This is in sharp contrast with the official teachings of a country where the top Islamic cleric said that 'children who do not read the Quran are with Satan and Satanic people.'

The situation in the most populated country in the region, Egypt, is far from being any better. Following a brief opening after the 2011 revolution, Egypt’s independent civil society organizations today face the most repressive environment in decades. Historically, autocratic governments in Egypt have selectively used civil society restrictions to ensure civic mobilization did not cross the ruling regime’s red lines. In contrast, Egypt’s new military government is using a multitude of tactics to undertake a much more comprehensive campaign to shrink civic space. Indeed, adding to the many cultural and political activists taken to prison with no clear charges, several cultural organizations have had to close their doors, amongst them two of the main artistic spaces of the country: Gudarn and Townhouse. Looking for an escape from this repression most activists, artists, researchers and curators have tried their luck in Europe, transforming one of its more dynamic urbes, Berlin, in the capital city of Arab exile.

Hammam Radio

(Berlin)

Hammam Radio is a hybrid project which springs from Hammam Talks — an initiative founded by Rasha Hilwi, Abir Ghattas and the staff of the be'kech in Berlin — and Radio Al Hay — an initiative launched by Majd Al-Shihabi and others in Beirut. Its launch coincided with the quarantine caused by the C-19 pandemic. The transformation and extension of Radio Al Hay to Hammam Radio from Beirut to Berlin is not out of relevance but is part of a pattern shaped by the forced exile of multiple Arab artists and intellectuals to the German capital. As expressed by Amro Ali On the Need to Shape the Arab Exile Body in Berlin 'For some time now, there has been a growing and conscious Arab intellectual community relocating there (...) feeding new political ideas, collective practices and compelling narratives that are currently being re-constructed and brought to life in a distantly safe city. Buttressed by the refugee waves, an intellectual flow of academics, writers, poets, playwrights, artists, and activists, among others, from across the Arab world gravitated towards Berlin as sanctuary and refuge. A unique Arab milieu began to take form as new geographic, social, and cultural conditions necessitated a reconstruction of visions and practices. The exile body built on the embers and mediated on the ashes of a devastated Arab public left burning in the inferno of counter-revolutions, crackdowns, wars, terrorism, coups, and regional restlessness'.

In this context, breaking the boundaries of time and space Hammam Radio is meant to be a place where women in all their diversity meet, talk, think, and raise their voices. Any woman is free to book a time slot and curate it at will. Although dedicated to Arab-speakers, the radio is open to any other language too. 'Hammam Radio' is one of the few spaces from where Arabs in exile to Europe can dance, sing, play music, read and tell stories to reflect and share time together.

In this context, breaking the boundaries of time and space Hammam Radio is meant to be a place where women in all their diversity meet, talk, think, and raise their voices. Any woman is free to book a time slot and curate it at will. Although dedicated to Arab-speakers, the radio is open to any other language too. 'Hammam Radio' is one of the few spaces from where Arabs in exile to Europe can dance, sing, play music, read and tell stories to reflect and share time together.

Besides the small number of cultural spaces in which the journey between the Same and the Other succeeds to reach a common ground, what has characterized government policies in both sides of the Mediterranean during the last decades has been the redefinition of nation-states in neocolonial and identity terms and a return to the idea of physical frontier as a condition for the restoration of national identity. The design of these new borders, which in the Arab world has its origin in the infamous 1916 Sykes–Picot agreement, does not aim only to safe-guarded nationalism, but to impose necro-political measures through the application of murdering techniques.

︎︎︎The Sykes–Picot Agreement was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire.

︎︎︎Over 1,100 people died attempting the crossing the Mediterranean sea towards Europe in 2018. In Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)

In this process, the 1985’s Schengen Agreement was a crucial event in the decision to build up an European indently. This immune community rests on a paradox: the fictionalization of an Europe that is opened to the free mobility of the Same, but builds up borders to protect itself from a invented Other. Closely related to both the phenomenon of migration — currently considered illegal as a result of the creation of Fortress Europe — and its touristic exploitation, the Mediterranean continues to be a liminal space. One that is crisscrossed by the hopes and speculations of thousands of individuals. Despite sharing the practice of travel, they confront opposite realities. As Zygmunt Bauman argues in Globalization: The Human Consequences,

in contemporary societies, the practice of travel has become polarized. Some travel by choice, others are forced to leave their homes and families. The former is expected and received with all kinds of attention and comfort. For the latter, the journey is illegal and, if they reach the destination, are treated with hostility and forced to confront a reality marked by indifference or xenophobia.

This polarization has profound cultural and psychological consequences; these are what Bauman calls the experience of the 'tourist' and the 'vagabond.' The disparity between these two traveling experiences takes in the current context a dramatic turn - one which, despite our beloved blindness, is continuously manifest.